Tax-Efficient Structuring for Cross-Border Exits

When selling a U.S.-based company to an international buyer or transferring assets across borders, tax structuring is critical to avoid unexpected costs. With evolving rules like the OECD’s Pillar Two minimum tax and the EU’s Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive, businesses face stricter compliance and higher tax risks if they don’t plan ahead. Here’s what you need to know:

- Direct Share Sales: Simple and tax-efficient for shareholders, especially with long-term capital gains or QSBS benefits. However, C-Corporations face double taxation.

- Asset Sales: Allows a step-up in asset value but triggers immediate taxes on unrealized gains, especially for intangible assets.

- Holding Companies: These reduce withholding tax rates via tax treaties but require proof of real operations (offices, employees) in the jurisdiction.

- IP Holding Structures: BEPS rules demand local substance and compliance, limiting benefits of low-tax jurisdictions.

- Cross-Border Mergers: Complex due to U.S. ownership thresholds under Section 7874, requiring substantial foreign operations to qualify.

Key takeaway: Early tax planning and compliance with global regulations are essential to minimize tax liabilities and ensure a smoother exit. Work with experts to align your structure with your exit goals and avoid costly mistakes.

Navigating Cross-Border Taxes

1. Direct Share Sale by Operating Company Shareholders

When exploring cross-border exit strategies, direct share sales often emerge as a straightforward option with notable tax advantages. In this approach, the buyer purchases shares directly from the shareholders, leaving the operating entity itself unchanged. For U.S. growth-stage companies, this method is particularly appealing because sellers may qualify for long-term capital gains treatment if the shares have been held for over a year.

This structure works especially well for S-Corporations and LLCs taxed as partnerships since these entities avoid taxation at the corporate level. In contrast, C-Corporations face double taxation - once at the corporate level and again at the shareholder level - making direct share sales less attractive for them. Additionally, ordinary income is taxed at higher rates than capital gains or qualified dividends, further underscoring the appeal of this strategy for certain entities [3]. Its straightforward nature also makes it a useful baseline for comparing more intricate structuring options.

For eligible shareholders, Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) under Section 1202 can potentially eliminate or significantly reduce capital gains taxes. However, meeting the requirements for QSBS - such as minimum holding periods and specific business activity criteria - can be challenging [2]. S-Corporation shareholders must also ensure compliance with key rules, like maintaining fewer than 100 shareholders and avoiding nonresident alien shareholders. Failing to meet these requirements could lead to automatic conversion to C-Corporation status, resulting in double taxation [3].

The international tax landscape adds further complexity. The OECD's Pillar Two framework introduces a 15% global minimum tax for multinational enterprises with revenues exceeding €750 million, expected to impact about 90% of large multinationals by 2025 [1][4]. Additionally, the BEPS Multilateral Instrument includes the Principal Purpose Test (PPT), which denies treaty benefits if tax avoidance is deemed the primary goal [5]. Eversheds Sutherland emphasizes the evolving challenges:

"tax treaties are no longer an automatic shelter; tax authorities worldwide share information and are quick to challenge arrangements that look like 'treaty shopping'" [1].

Beyond selecting the right structure, companies must navigate rigorous compliance requirements. For instance, foreign shareholders need to provide updated Form W-8BEN or W-8BEN-E to claim reduced withholding rates under tax treaties. Without these forms, payments could be subject to the standard 30% U.S. withholding tax [6]. Additionally, firms must maintain robust transfer pricing documentation and demonstrate genuine economic substance - such as having real offices, employees, and decision-making authority in the claimed jurisdiction - to meet regulatory expectations [1][7].

2. Asset Sale with Reinvestment and Post-Exit Reorganization

An asset sale with post-exit reorganization involves selling specific company assets - rather than shares - followed by restructuring operations across borders. While this approach allows for a step-up in the tax basis of the assets, it also comes with hefty immediate tax liabilities for sellers[8]. For U.S. growth-stage companies, this strategy can be far more complicated than simpler exit methods.

One major hurdle is the exit tax on asset transfers. According to Section 367 of the U.S. tax code, transferring assets out of the U.S. is treated as a taxable event, regardless of the foreign corporation’s status. This means unrealized gains are taxed immediately[10]. Intangible assets like patents, trademarks, and proprietary technology face even stricter rules under Section 367(d), which treats these transfers as if they were sales tied to future earnings[9]. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made this even tougher by removing the "active trade or business" exception for tangible property, exposing most asset transfers to immediate taxation[10].

On top of the tax challenges, there are significant administrative requirements. Companies must file Form 926 to report the fair market value, adjusted tax basis, and recognized gain for all transferred assets[10]. Failing to file can lead to penalties of 10% of the transferred property's value, capped at $100,000 unless the omission is intentional[10]. Additionally, if cash or other property (referred to as "boot") is received in the exchange, it accelerates the tax liability into the current year under Section 367(d)[9].

International tax rules add another layer of complexity. For companies subject to the OECD's Pillar Two framework - those with revenues exceeding €750 million - the 15% global minimum tax limits the benefits of reinvesting in low-tax jurisdictions post-exit[1]. Even with careful planning, these reorganizations often fail to deliver the anticipated tax savings. The combination of immediate taxation, intricate reporting obligations, and increased anti-avoidance measures makes this route especially challenging for U.S. growth-stage companies aiming for a smoother exit. These obstacles highlight the importance of crafting a well-thought-out exit strategy tailored to the unique challenges of cross-border transactions.

3. Holding Company Structures in Treaty Jurisdictions

Setting up a holding company in a treaty jurisdiction can help significantly lower the tax burden on cross-border exits, but it requires careful planning and ongoing management. One of the key benefits is the potential to reduce or even eliminate withholding taxes on dividends, interest, and capital gains. For example, without treaty protection, a non-U.S. corporation operating in the United States might face a combined federal tax rate as high as 44.7%. This includes a 21% tax on effectively connected income and a 30% branch profits tax on equivalent dividend amounts [11]. However, with the right treaty structure in place, the branch profits tax can drop to as little as 5% or even 0% [11]. This makes treaty-based planning an attractive option for many businesses.

Reverse foreign hybrids (RFHs) are a great example of how treaty benefits can be accessed without adding U.S. filing obligations. These entities are treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes, but they remain tax transparent in their home jurisdiction. This allows the ultimate owners to claim treaty benefits without having to file individual U.S. tax returns [11]. As Mayer Brown explains:

"The RFH structure provides treaty access, while also enabling investors to avoid the requirement to file a U.S. tax return" [11].

Modern U.S. tax treaties often include provisions for tax-transparent entities, allowing treaty benefits to flow through to the owners if they "derive" the income under the laws of their home country. A September 2025 IRS General Legal Advice Memorandum confirmed that these provisions apply to business profits, offering more clarity for companies using RFH structures [11].

To qualify for treaty benefits, holding companies must meet Limitation on Benefits (LOB) rules, which are designed to prevent treaty shopping. This typically involves proving genuine economic activity in the treaty jurisdiction. For example, companies may need to maintain a physical office (not just a registered address), employ local staff, and hold board meetings in the jurisdiction where key decisions are documented. Many treaties also require at least 50% local ownership, and the OECD’s Principal Purpose Test can deny treaty benefits if the primary goal is tax avoidance.

Operating a holding company also comes with significant compliance requirements. For U.S. growth-stage companies, the administrative workload can be heavy. This includes local statutory audits, maintaining separate accounting records, managing local payroll, and covering recurring legal fees for corporate secretarial services. Additionally, companies must meet a 12-month residency requirement for branch profits tax relief, which is typically assessed on the last day of the entity’s tax year [11]. Under BEPS Action 5, holding companies must demonstrate substantial local operations, and for IP-related holdings, there must be a clear connection between the income and related R&D activities. Furthermore, the fixed ratio rule under BEPS Action 4 limits net interest deductions to 30% of EBITDA, preventing companies from overloading subsidiaries with debt to reduce taxable income [12][13].

The decision to adopt this structure depends on factors like the projected exit value and timeline. For exits expected within 12 to 18 months, the costs of establishing and maintaining the necessary substance might outweigh the tax savings. On the other hand, for companies with longer-term plans and substantial cross-border cash flows, setting up a holding company in jurisdictions like Luxembourg, the Netherlands, or Ireland can provide significant tax efficiencies - so long as the compliance framework is established early.

For U.S. growth-stage companies, consulting with experts like Phoenix Strategy Group (https://phoenixstrategy.group) can be essential in navigating these complexities and ensuring a tax-efficient cross-border exit strategy.

sbb-itb-e766981

4. Intermediate IP or Principal Companies Under BEPS Constraints

Using an intermediate company to hold intellectual property (IP) for tax advantages has become increasingly challenging due to BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) regulations. The straightforward days of placing IP in a low-tax jurisdiction and collecting royalties are over. Now, tax authorities scrutinize where the actual work happens - not just where legal documents claim the IP resides. This shift differs from other holding company structures that focus more on treaty benefits than on IP-specific issues.

The DEMPE framework - Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection, and Exploitation - now dictates how IP is valued and taxed. Essentially, the jurisdiction where the IP is held must show real substance. This means having local personnel who make key decisions, manage the IP, and oversee R&D activities. As the OECD reports:

"BEPS practices cost countries USD 100-240 billion in lost revenue annually. That is equivalent to 4-10% of global corporate income tax revenue" [14].

With such significant losses, over 140 countries are actively working together to close these tax loopholes.

For U.S. growth-stage companies, the tax advantages of relocating IP have significantly diminished. The Pillar Two global minimum tax establishes a 15% floor, making traditional low-tax jurisdictions less attractive. On top of that, supplementary taxes like the GILTI regime (around 13.125%) may still apply. In June 2025, the U.S. Treasury Secretary and G7 partners announced a "side-by-side" solution, exempting U.S.-parented groups from other countries' Pillar Two taxes - but only if the U.S. drops the proposed IRC Section 899, which could increase U.S. tax rates on foreign-source income by up to 20 percentage points [15]. This agreement underscores the complexity of today’s tax environment.

The compliance requirements are also significant. Companies must file GloBE Information Returns, maintain detailed transfer pricing documentation (e.g., Master Files and Local Files), and submit Country-by-Country reports detailing income, taxes, and business activities. To meet local substance requirements, businesses need to employ staff, maintain physical offices, and demonstrate local decision-making through operational activities. For U.S. companies planning near-term exits, these administrative and operational burdens might outweigh the potential tax savings. However, businesses with a longer-term outlook and high-value IP may still benefit - provided they commit to building and sustaining the necessary local presence.

5. Cross-Border Mergers, Inversions, and Redomiciliation Structures

Cross-border mergers and inversions offer a complicated yet viable path for U.S. companies aiming to relocate operations abroad for tax purposes. However, Section 7874 of the U.S. tax code imposes stringent ownership rules that can disrupt these plans. For instance, if former U.S. shareholders end up owning 80% or more of the foreign acquiring company, the IRS will treat the foreign entity as a U.S. corporation for tax purposes, effectively erasing the anticipated tax benefits [17]. If ownership falls between 60% and 80%, the foreign corporation retains its status, but the U.S. company faces restrictions, including a 10-year prohibition on using net operating losses or tax credits to offset inversion gains [18]. These thresholds are just the beginning of the challenges posed by inversion rules.

The IRS has tightened regulations to close loopholes that previously helped companies meet these ownership thresholds. For example, the Passive Assets Rule excludes stock derived from cash or marketable securities, preventing companies from artificially reducing U.S. ownership by overloading foreign entities with liquid assets [17]. Similarly, the Non-Ordinary Course Distribution (NOCD) Rule scrutinizes distributions made by a U.S. company in the 36 months before an inversion. Excessive distributions are added back to the company's value, increasing the chance of breaching the 60% or 80% ownership limits [17]. Additionally, the Serial Acquisition Rule prevents foreign corporations from using multiple U.S. acquisitions over a three-year span to create a platform for larger inversions [19].

Beyond ownership thresholds, other rules add layers of complexity. The Substantial Business Activities Exception requires the expanded affiliated group to prove that the foreign parent company has legitimate operations in its home country. According to the 2018 Regulations, the foreign parent must qualify as a "tax resident", meaning it must be subject to local tax laws as a resident entity, even if the jurisdiction does not impose corporate income tax [17]. This means the foreign parent must have actual employees, assets, and management in the host country rather than functioning as a shell company. For many growth-stage companies, meeting these requirements can be both administratively challenging and impractical for short-term goals.

The Third-Country Rule introduces yet another hurdle. If a U.S. company merges with a foreign target under a new parent entity based in a third country chosen for its tax advantages, the IRS can disregard stock issued to the foreign target's shareholders. This can push U.S. ownership above the critical 80% threshold, forcing companies to consider the foreign target’s home country rather than a tax-friendly jurisdiction [17][18]. As Wilson Sonsini explains:

"The 2018 Regulations replace the phrase 'subject to tax as a resident' with 'tax resident,' which the 2018 Regulations define as 'a body corporate liable to tax under the laws of a country as a resident'" [17].

For U.S. growth-stage companies, these rules create a heavy administrative burden. Companies must track all distributions over the three years leading up to a transaction, audit any domestic acquisitions from the past 36 months, and ensure the foreign parent meets tax residency criteria [17]. A 5% de minimis exception exists if former U.S. shareholders hold less than 5% of the foreign entity post-transaction, but this typically requires a cash purchase rather than a stock swap [17][18]. Given these challenges, inversions are generally more practical for larger, well-established companies that can navigate the regulatory maze and establish substantial foreign operations.

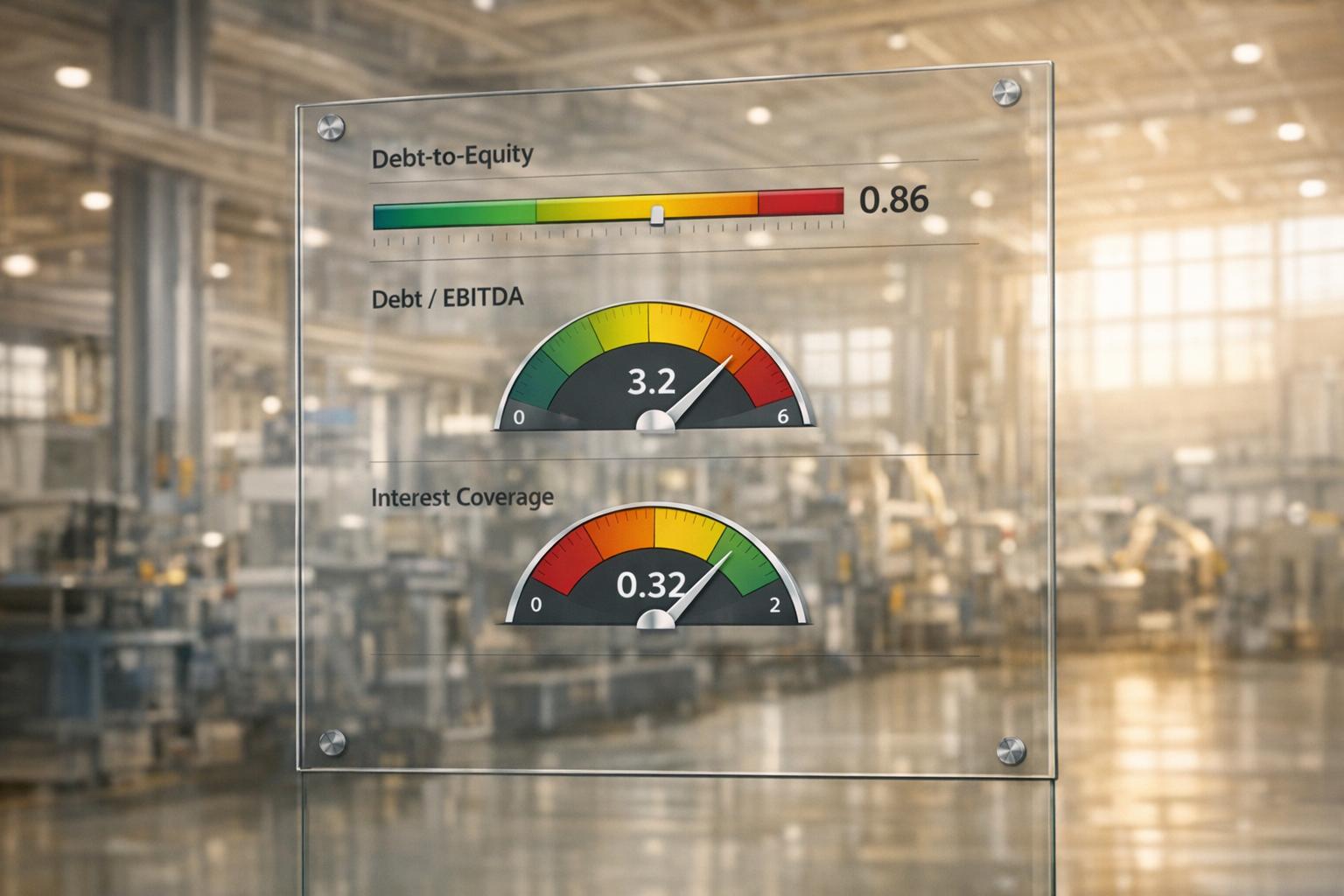

Comparison of Structuring Options

Cross-Border Exit Structuring Options: Tax Efficiency and Complexity Comparison

This section breaks down and compares key structuring options for cross-border exits, highlighting their pros and cons to help you find the right balance between tax considerations and regulatory hurdles.

When it comes to straightforward exits, direct share sales stand out. They’re particularly attractive to founders, given the favorable long-term capital gains tax rates (0% to 20%)[2]. This option works best when Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) benefits apply and the subsidiary avoids being classified as a US Real Property Holding Corporation (USRPHC). As Anthony C. Infanti from the University of Pittsburgh School of Law points out:

"The manner in which an inbound investment is initially structured can greatly impact the tax cost that will be incurred by the foreign client when he/she/it sells or disposes of (i.e., 'exits') the proposed inbound investment"[24].

For those looking to reduce withholding taxes on dividends, interest, and royalties, holding company structures are worth considering. These structures leverage Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAAs)[21][22]. However, they come with a hefty price tag in terms of setup and ongoing compliance costs. Meeting OECD BEPS requirements often means establishing physical offices, hiring local employees, and demonstrating decision-making activities[20][22]. While this complexity may be justified for multinational corporations managing intricate intellectual property (IP) flows, it may be overkill for simpler exits or individual founders.

Intermediate IP structures, on the other hand, must navigate the complexities of BEPS 2.0. These structures are subject to the 15% global minimum tax, which is calculated on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis. This requires meticulous tracking of effective tax rates (ETRs) and may trigger additional top-up taxes. As Adam Sweet from EY explains:

"The global minimum tax is vast in both its reach and complexity, with rules that define a new tax base and a nuanced formula to calculate minimum top-up tax on a jurisdictional basis"[16].

The compliance demands here are significant, often requiring overhauls to tax processes and systems to handle the granular data needed for reporting[16].

Asset sales, meanwhile, face challenges like ordinary income tax and the risk of double taxation. For cross-border mergers and inversions, compliance with Section 7874 rules, passive asset limitations, and substantial business activity requirements adds layers of complexity[17][18][22][23]. Historically, tax rates on cross-border dispositions have reached as high as 35%, making early tax modeling crucial for maximizing after-tax returns[24][20].

Here’s a quick comparison of these structuring options:

| Structuring Option | Tax Efficiency | Setup Complexity | Ongoing Costs | Substance Requirements | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Share Sale | High (0%–20% capital gains)[2] | Low | Minimal | Low | Individual founders, simple exits[23] |

| Holding Company | High (treaty-based withholding reduction)[21][22] | High | High | High (office, employees, local decisions)[20][22] | Multinational groups, complex IP flows[22] |

| Intermediate IP/Principal | Moderate (subject to 15% minimum tax)[16] | Very High | Very High | Very High (jurisdiction-specific ETR tracking)[16] | Large MNEs with revenues >€750M[16] |

| Asset Sale | Low (ordinary income on certain assets)[22][23] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Buyer-favorable scenarios[23] |

| Cross-Border Merger/Inversion | Variable (depends on Section 7874 compliance)[17][18] | Very High | High | Very High (substantial business activities)[17] | Large, established companies[17] |

This table consolidates the main considerations, offering a clear snapshot of the trade-offs involved in each option.

Conclusion

Navigating a cross-border exit requires careful tax planning from the outset. Without a well-thought-out strategy, your overall tax burden can balloon, potentially making your business less competitive than before[26]. As Anthony C. Infanti from the University of Pittsburgh School of Law points out, the way you structure your initial investments plays a big role in determining the tax costs you'll face during an exit[24]. The sooner you align your business structure with your exit goals, the better.

For U.S. companies, integrating tax planning with operational strategies early on is essential. Your business structure should reflect your exit objectives, whether you're aiming for an IPO, a strategic acquisition, or another pathway. For example, you need to decide how cash will be handled: Will it be repatriated to pay down debt, or kept offshore to fuel expansion?[26] Delaying these decisions until the exit process begins can lead to costly mistakes, such as exposure to withholding taxes or double taxation that erodes value.

The regulatory environment is also evolving rapidly. With the implementation of Pillar Two's global minimum tax and stricter BEPS compliance requirements, companies must move from theory to action[25]. This involves preparing tax teams early, documenting transfer pricing with arm’s-length evidence, and meeting substantial business activity standards if you're using holding company structures. For instance, the FDII deduction can reduce your effective tax rate on qualifying export income to 13.125%[26], but only if your intellectual property and operations are structured correctly.

Without the protection of tax treaties, your effective tax rate could exceed 50% due to double taxation[26]. This makes it critical to work with advisors who are well-versed in both U.S. tax laws and the regulations of your target jurisdictions. Skilled advisors can simplify compliance and help you avoid pitfalls[27]. For example, Phoenix Strategy Group offers M&A advisory services tailored to help growth-stage companies navigate these complexities, ensuring their financial structures align with their exit strategies.

The takeaway is clear: start planning early, factor tax considerations into every strategic decision, and maintain strict compliance throughout. Companies that treat tax structuring as an afterthought often pay the price when it’s time to exit. On the other hand, those that build tax efficiency into their foundation from the beginning can maximize after-tax returns and position themselves strongly for future opportunities.

FAQs

What are the main tax differences between selling shares and selling assets in a cross-border exit?

When selling assets in a cross-border exit, the seller might be subject to ordinary income tax rates - which can go as high as 37% - on certain assets. Unfortunately, opportunities to qualify for capital gains treatment in this scenario are quite limited. That said, this setup can work in the buyer's favor by providing a step-up in basis, which helps reduce future tax liabilities through depreciation.

Alternatively, selling shares (or stock) often allows the seller to benefit from capital gains tax rates, which are generally lower than ordinary income rates. This method also sidesteps double taxation. However, it doesn't give the buyer a step-up in basis, which could limit their potential tax advantages. Deciding on the best structure involves weighing tax considerations, compliance needs, and overall strategic objectives.

How can holding companies help minimize withholding taxes in cross-border transactions?

Holding companies are often set up in locations that offer tax treaties with more favorable terms. These treaties can lower the withholding tax rates on payments such as dividends, interest, or royalties sent to the holding company, which might otherwise face higher domestic tax rates. This setup can help businesses reduce the overall tax impact on cross-border transactions.

Using these treaty benefits allows companies to align their operations with international tax standards while improving tax efficiency. That said, it's crucial to adhere to anti-tax avoidance laws to ensure the structure stays compliant and legally secure.

What challenges do intermediate IP holding structures face under BEPS regulations?

Intermediate intellectual property (IP) holding companies are often used in cross-border exits to consolidate valuable assets like patents, trademarks, or software in jurisdictions with lower tax rates. However, the OECD-G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) framework, particularly Pillar Two, has introduced stricter rules aimed at curbing tax avoidance. Under this global minimum tax regime, these entities must prove they have real economic substance - such as employing adequate staff, maintaining premises, and conducting active R&D - or face additional taxes through a top-up rate.

Here are some of the main challenges:

- Substance requirements: To avoid extra taxes, IP holding companies need to meet the OECD's substance criteria, which can include demonstrating genuine operational activities.

- Blended income taxation: Income streams like royalties may lead to top-up taxes if the effective tax rate in the jurisdiction falls below the 15% threshold.

- Compliance complexity: Companies must handle intricate reporting obligations, maintain thorough documentation, and keep a close eye on tax rates across different jurisdictions.

Dealing with these challenges often calls for specialized tax knowledge and advanced tools to balance compliance needs with tax efficiency.